Current Research

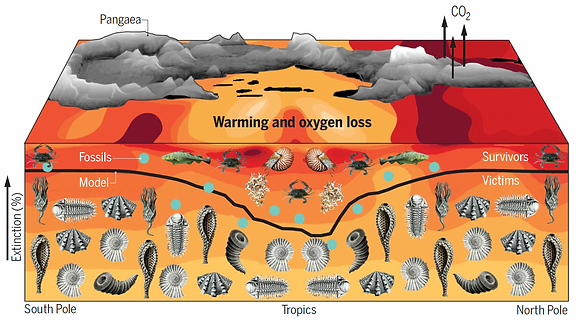

Figure: Penn et al., 2018, depicting their model of temperature-dependent hypoxia as a driver of the end-Permian marine mass extinction.

The end-Permian mass extinction (~252 million years ago) was the most taxonomically and ecologically severe extinction event to have occurred in the fossil record. It was triggered by a large province of volcanoes erupting, which choked the oceans with so much sulfur and carbon dioxide that the oceans became much hotter and less hospitable to life for many animals. This event is colloquially known as the "Great Dying".

It's been warned that taxonomic homogenization is also starting to occur in the modern. My ongoing research aims to uses the fossil record to help shed light on how this may be occurring in the oceans, and if so, aims to determine its current and potential spatial and temporal extent.

My research is two-fold:

-

A large part of it involves combining data from paleontology (which tells us about which animals lived at a particular time, and where) with data from geochemistry ( which tells us about oceanic oxygen and temperature); and physiology (which tells us about how well animals can withstand changes in oceanic temperature and oxygen) to provide a mechanistic model to explain patterns of extinction and biogeographic change that we see after environmental perturbations.

-

The other portion of my research involves taxonomically identifying the fossils of bivalves (i.e. oysters and clams) which my collaborators and I have collected in central Saudi Arabia for the Lower Triassic, and which represent what marine communities might have been like following the wake of the most devastating mass extinction known as the end-Permian mass extinction. Ongoing research will pivot to more recent fossils to see how bivalve communities have responded to human activities.

![Selectivity of mass extinctions-4[88].png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/f339c1_145bb3e0c0774a4989ee75fac966a306~mv2.png/v1/crop/x_0,y_0,w_2239,h_2250/fill/w_471,h_476,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/Selectivity%20of%20mass%20extinctions-4%5B88%5D.png)

I drew this graphical abstract for a paper I coauthored to explain how we examine patterns in past extinction events (and the recovery of ecosystems afterwards) with processes related to organismal physiology and changes in oceanic temeperature and oxygen. Much of the work I do involves investigating potential links of biogeographic recovery patterns of benthic marine ecosystems to these physiological concepts.

Along with biogeographic and paleo-ecological analyses, I am training to taxonomically identify bivalves (ex: clams), gastropods (ex: snails) and brachiopods from my study area and period. These are not my study specimens, but I snapped a pic of these lovely fossil bivalves during a field trip with our interns in Capitola beach, CA. These fossils are 5 million years old!

My work mainly involves marine invertebrate fossils, namely mollusks such as clams and snails. These fossils are globally widespread and have a rich stratigraphic record, which means their fossil record spans much of the 542 million year history of visible life.

My father, a retired professor who specializes in stratigraphy, worked on the stratigraphy of the same site I am sampling my fossils from (40 years ago!) and lent his expertise in the area and collaborated with us on one of my projects in Saudi!